Conditional Operations in Object Stores

Published:

tl;dr

Since S3 introduced strong(er) consistency in 2020 and conditional writes in late 2024, table formats like Apache Iceberg can assume stronger guarantees from object storage. Stricter consistency guarantees were already supported by Azure and GCS1. How do conditional operations perform under load?

We benchmark the atomic/conditional primitives that object stores provide across AWS S3 and S3 Express One Zone, Azure Blob (Standard and Premium), and Google Cloud Storage.

| Object Store | Compare-and-Set (op/s) | CAS Latency (ms) | Append (op/s) | Append Latency (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

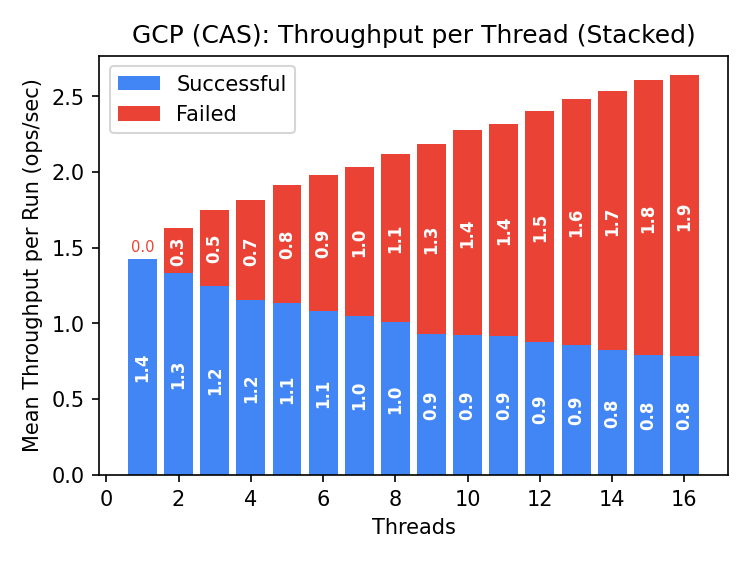

| GCS | 0.8-1.4 | 500-700 | – | – |

| Azure (Standard) | 9.2-10.2 | 100-600 | 9.2-10.2 | 90-100 |

| Azure (Premium) | 15.3-16.6 | 60-350 | 11.1-11.4 | 70-74 |

| S3 | 14.7-15.3 | 58-68 | – | – |

| S3X | 68.6-75.3 | 14-26 | 71.0-94.1 | 14-24 (9800-10400)* |

*S3 Express One Zone (S3X) lazily composes appends on read; see details below.

See the graphs for detailed throughput and latency analysis.

Conditional operations are useful building blocks for coordination through storage, but object stores are not designed to be consensus systems2. Storage-only coordination is limited to low throughput workloads without an intermediary service to batch and order operations.

Conditions for Coordination in Storage

I just dropped in to see what condition my condition was in

The ostensible Future of Data Systems is a converged data lake. Vendors build toward this vision in path-dependent ways, but table formats like Apache Iceberg are emerging as a common substrate for interoperability with limited (or no) coordination between systems outside of storage.

In the 2010s, we pretended that eventual consistency was usable because it was cheap. Iceberg made the elegant partition of its strongly-consistent Catalog state and the eventually-consistent object store where data and metadata files are stored. Transactions following a pointer from the catalog accessed a fixed, immutable set of objects; the only eventual state to reconcile was an object’s transition from absent to present. From an application perspective, this is like transforming a consistency problem- reasoning about which updates have been applied- to an availability problem- parts of a table snapshot might be temporarily missing.

Modern object stores provide stronger consistency guarantees and atomic operations over objects. So… is any of this useful to the design of table formats? Let’s measure the practical limits of conditional/atomic operations in object stores. They are the building block for linearizable swaps and commit protocols in an open, storage‑only catalog3.

Conditional Operations

Skip to measured results if you don’t want to read a primer on conditional operations.

In a nutshell, clients updating an object provide a token from data they read earlier to the object store, which rejects that write if the token doesn’t match the current state. In a table format, the application coordinating the transaction is saying, “I checked the table in state x. Only apply my update if the table is still in state x; otherwise leave the state of the table unchanged so I can retry, fail, or wander off forever.”

“Wandering off forever” is particularly important for table formats, since concurrent transaction processors could have wildly different resource constraints. The bloated corpse of a large, failed transaction could prevent writers with fewer resources from making progress if they first need to clean up the failed transaction.

Consider two typical Iceberg clients: Florence: a Spark job enriching tens of terabytes of table data using hundreds of nodes and Bob: inserting kilobytes of data from a streaming source. If Florence wanders off, nobody thought to provision Bob with the resources to undo/redo even a fraction of Florence’s work. Installing updates with a single, conditional operation avoids any dependencies between uncommitted transactions that might entangle their resources. It’s a key idea in Iceberg’s design4: all work preparing a transaction is completed outside the table before installing it at commit.

Three widely supported conditional operations could enable linearizable updates from uncoordinated writers to a single object.

If-absent

This is probably the most widely available conditional operation. Basically, “write this object only if it does not already exist”. With a naming convention for successors, one can order updates by probing for the latest version and writing the next version in the sequence. Obvious example: if the transaction depends on objname.x then attempt to write objname.(x+1). Some implementations store a recent-ish version that clients blindly overwrite in race after a successful commit, to provide a hint for the “tail” of the log.5

I didn’t evaluate this operation as its performance under the synthetic benchmark would be unrealistically pessimistic. Without retries or backoff, each writer would require multiple round trips to discover the current version before attempting its write. The benchmark would tell us less about the capabilities of the object store than the efficiency of the tail-locating protocol.

If-match

Every object is associated with a nonce that uniquely identifies the object at that location. The implementation of a compare-and-set (CAS) is straightforward: keep the nonce- an entity tag (etag; S3 or Azure) or generation (GCS)- when the object is read and provide it to ensure the correct version of that object is overwritten6. The write checksum must also protect against partial writes (e.g., closing the stream while unwinding the stack could replace the old version with a partially-written object).

The read-modify-overwrite loop makes this approach impractical as the object gets larger; the read costs get too high. Moreover, not all stores guarantee that concurrent readers can even complete the object read if it is interrupted by an overwrite. Readers should be protected from torn reads (i.e., reading a prefix of one version of the object and the suffix of its successor), but I’ve heard of widely used storage systems that failed to provide this basic protection.

Atomic Append

Object stores usually warehouse immutable objects, but Azure Blob Storage and S3 Express One Zone (S3X) support appending data to an existing object7. Both implement a conditional, position-based append: the client reads the current length of the object and attempts to write its data to that offset. As long as it’s the same base object, an append that fails the position check can be retried with the new length, avoiding the costs of reading and merging required by a compare-and-set.

Contrast this with POSIX O_APPEND or GFS/KFS/QFS record append. When the storage service owns the ordering of atomic appends, clients don’t need to know where the tail is when they append to an object. The service will fill holes if clients are slow or fail (avoiding partial writes) and assemble a contiguous object from the ragged tail of appends. Neither Azure nor S3X implement record append.

Instead, both Azure and S3X supply metadata for the clients to order their own operations. Conditional appends must match both the position and etag for the base object and include a checksum to ensure the full write succeeds. Limits on the size and number of appends per object apply: S3X allows up to 10,000 appends up to 5GiB each; Azure allows 50,000 appends up to 4MiB each.

Delegating append ordering to the client simplifies everything except the writer. Server side: replication and concurrent reads at the tail are much simpler if writes that are contiguous in the object arrive ordered. Slow or failed appends can’t be visible to external clients, so in an implementation of record-append: replicas need to handle cases where they disagree on the presence or content of a particular record. Not only in recovery, but in forward operation. Client side: readers also need to handle duplicate records. If a write times out, the writer can’t be certain if its append was applied or not. If the client retries, two duplicate records could be applied at distant offsets.

Acknowledging the implementation complexity, the storage service can reorder writes more efficiently than independent clients. As we’ll see in benchmarks, position append avoids the read and merge costs of CAS, but oblivious coordination across writers will limit its throughput.

Hereafter, I’ll refer to S3 Express One Zone as S3X and Azure with Premium storage as AzureX for brevity.

Performance

Benchmark setup (click to expand)

Throughput is measured using a custom YCSB client wrapping each cloud's Java SDK. The synthetic workload issues conditional updates against a single, 2KiB object _without retries or backoff_ to determine upper-bound throughput.

CAS operations read the full object before conditionally overwriting (reflecting real applications that merge state). Append workloads write 256-byte chunks until reaching 9900 appends (~2.4MiB), then reset via CAS. Measurements were taken in mid-June 2025.

To avoid intra-SDK side effects from caching, batching, and throttling, each client runs in its own JVM/process. Throughput and latency are measured over the time window when all JVMs ran concurrently: from the time the last client started to the time the first client finished. All runs used Ubuntu 20.04 images from the cloud vendor. Throughput and latency are averaged over five runs, each running for five minutes. I did not attempt to control for diurnal patterns or other known sources of variance, as we are concerned only with the broad differences between clouds and the viability of a shared storage architecture.

The benchmark models a roughly catalog-sized object in storage. This could be literally the Iceberg catalog, or really _any_ resource in object storage that concurrent, conflicting transactions need to update. If we allow conditional writes on the commit path, we want to know when they could become a bottleneck.

We used the following configuration (terraform scripts):

| Cloud | VM | Region |

|---|---|---|

| AWS | m5-4xlarge | us-west-2 |

| Azure | Standard-D16s-v3 | West US |

| GCP | n2-standard-16 | us-west1 |

CAS (Compare-and-Set)

Google Cloud Storage

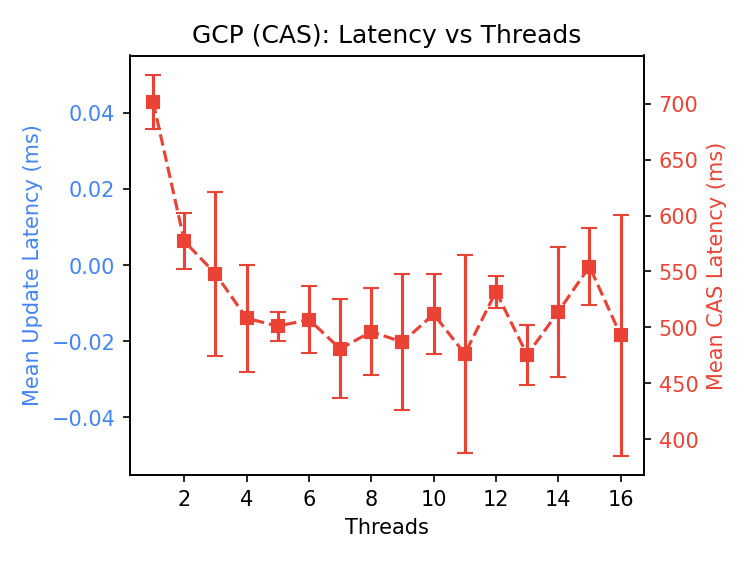

Kudos to the team responsible for throttling single-object requests. The single write per second limit is documented. Even the single-client CAS latency is over 700ms, which is quite high. I wrote the GCS team to verify that I was using the SDK correctly and had not overlooked a storage configuration suited to this workload, but did not receive a response.

Given the documentation, it seems likely that this is performing as designed. I did not modify the benchmark to use composite object support to emulate append, as I assume the same limit applies.

A guess: versioning support probably retains multiple versions of the data, and without throttling the system could be overwhelmed. It would be worth testing if larger objects can be read without interruption from concurrent writes e.g., a workload of readers starting 100ms apart, interrupted by a write every 2s. CAS operations in Azure sometimes interrupted readers.

Azure Blob Storage

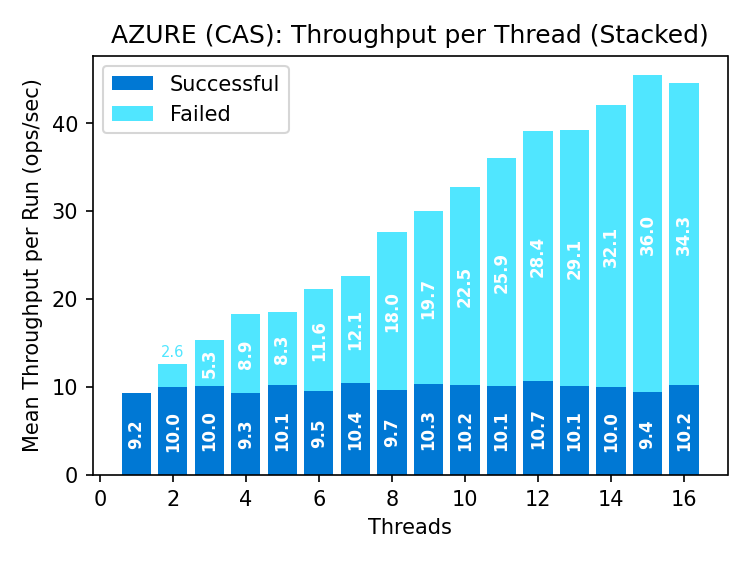

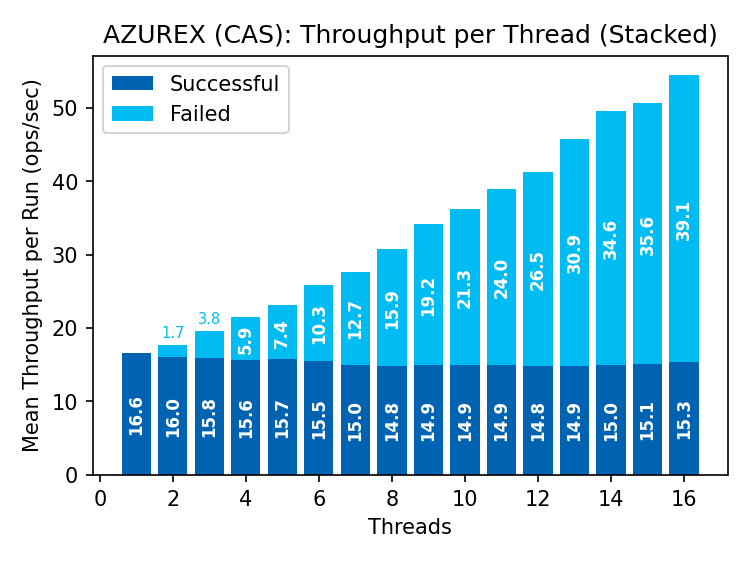

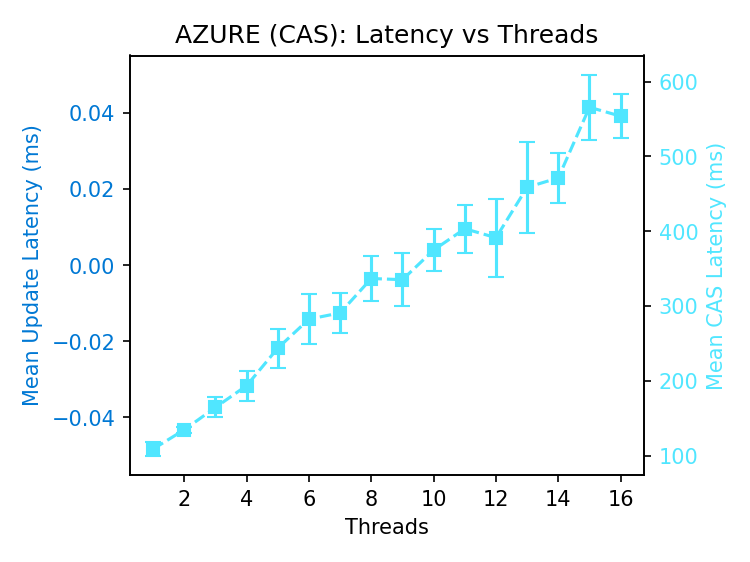

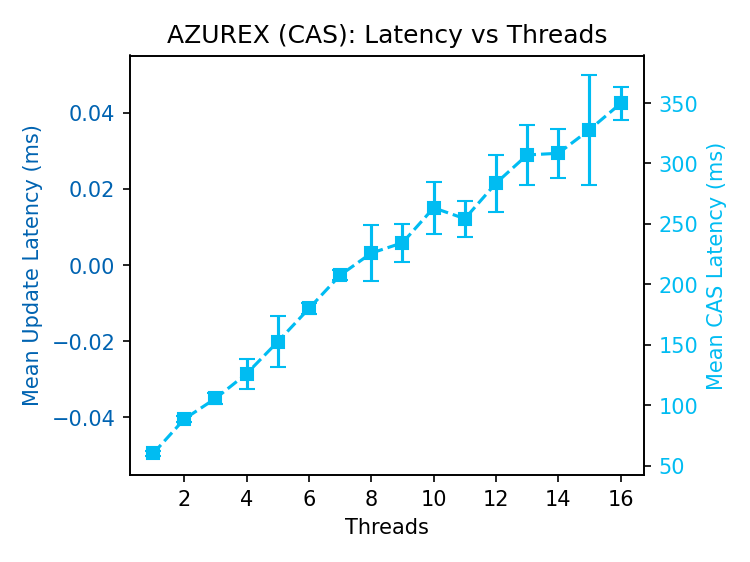

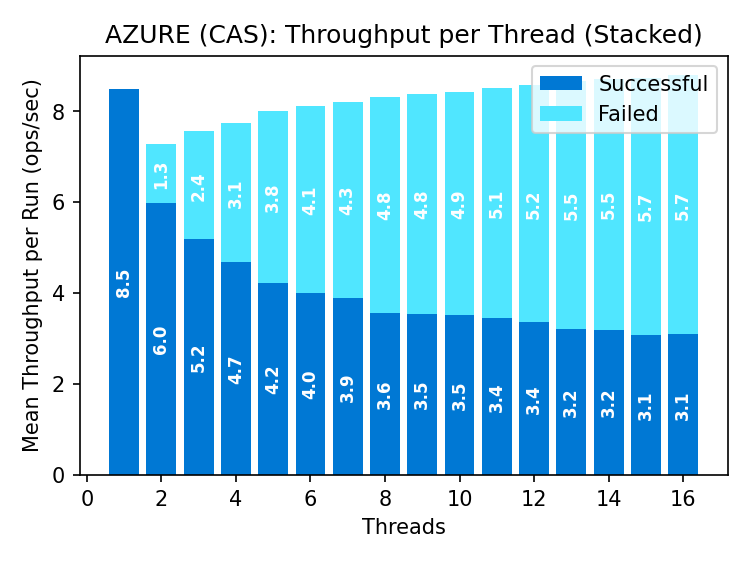

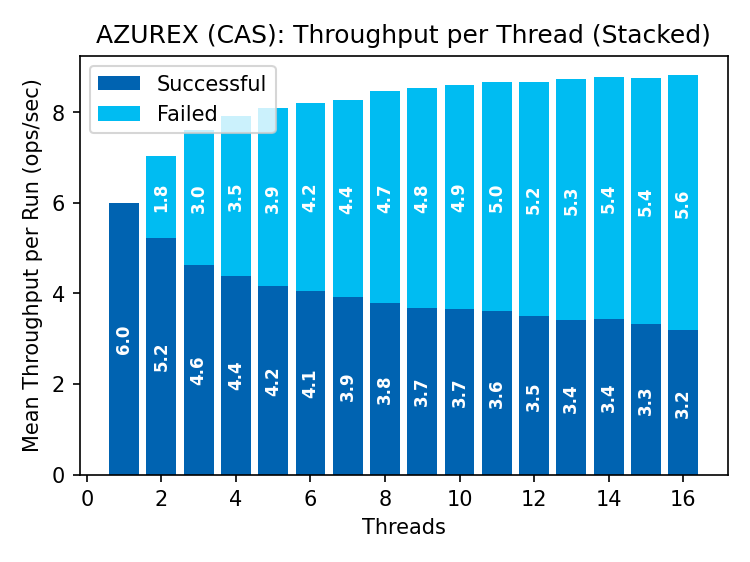

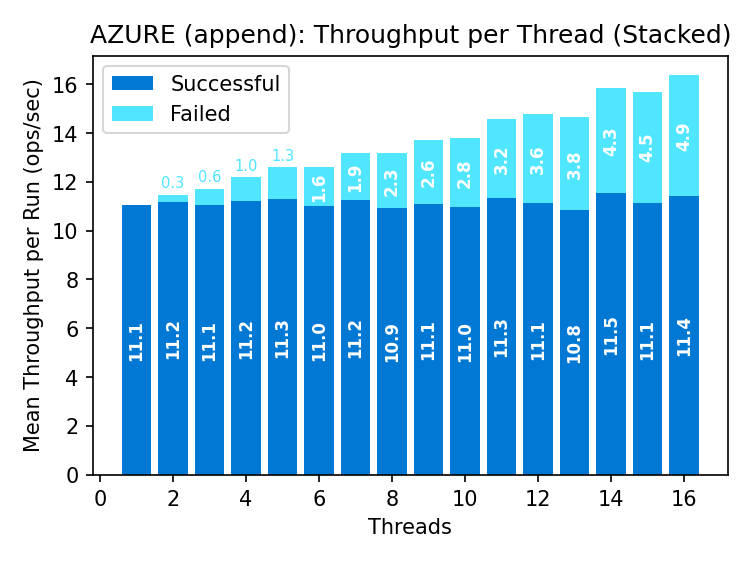

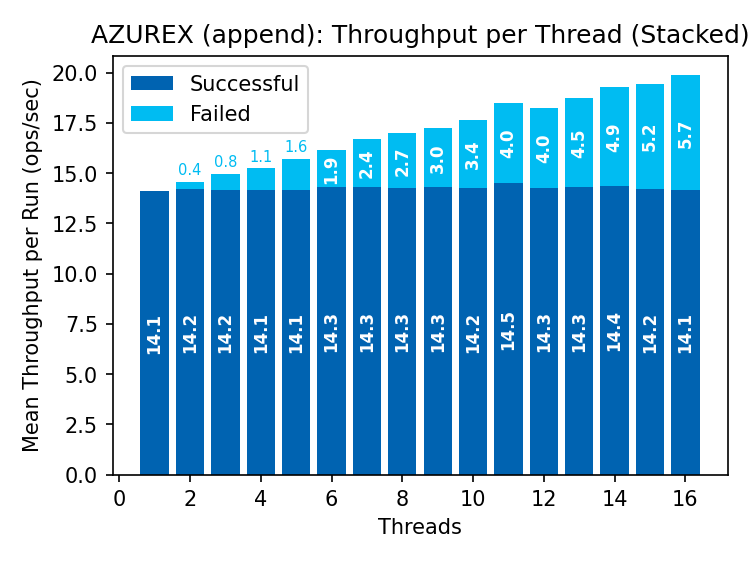

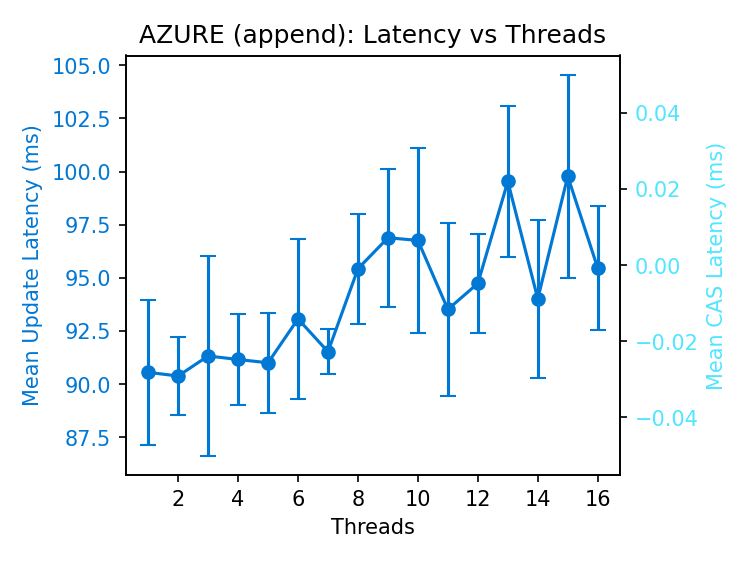

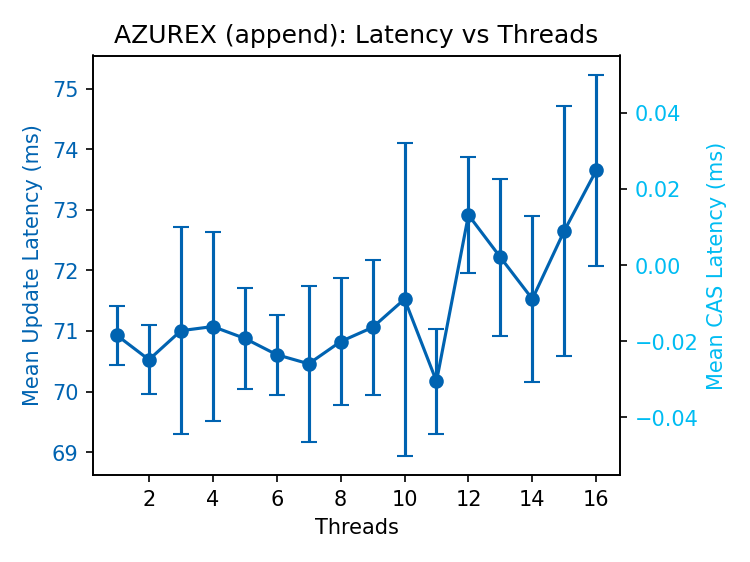

Goodput remains steady as the rate of failed operations increases with parallelism. Premium supports ~50% more goodput than standard storage.

A pipeline of conditional requests is mostly waste: a successful write invalidates all outstanding requests, so only one can succeed per round-trip. This fundamentally restricts conditional write throughput.

The increasing latency of successful operations in Azure is not innate to conditional writes. The benchmark does not retry failed requests; the increase in latency must be attributed to the store, as every client runs in its own process.

Azure Blob Storage had some odd behaviors worth noting, against the advice of my generous reviewers whose taste is otherwise impeccable.

Azure CAS anomalies (click to expand)

Anomalies

First, the length reported after a CAS is sometimes _zero_. This happens intermittently; subsequent reads return the correct length. It's unclear if this is a consistency issue, client bug, or a bug in my implementation, but this (invalid) state should not be visible to clients between CAS operations.

Second, CAS operations sometimes caused outstanding reads to fail, particularly in the append workload. These errors were infrequent, but this microbenchmark is on small data and reads of larger objects might be more susceptible to interruption by concurrent writes.

Third, throughput using SAS tokens (Shared Access Signatures that delegate access without exposing the storage account key) is significantly higher than the default authentication mechanism, as shown below. At high client counts, errors include timeouts from whatever ancillary service is authenticating requests. Creating different SAS tokens per client has no effect on throughput, so the throttling appears to be from the default auth service.

AWS: S3 and S3X

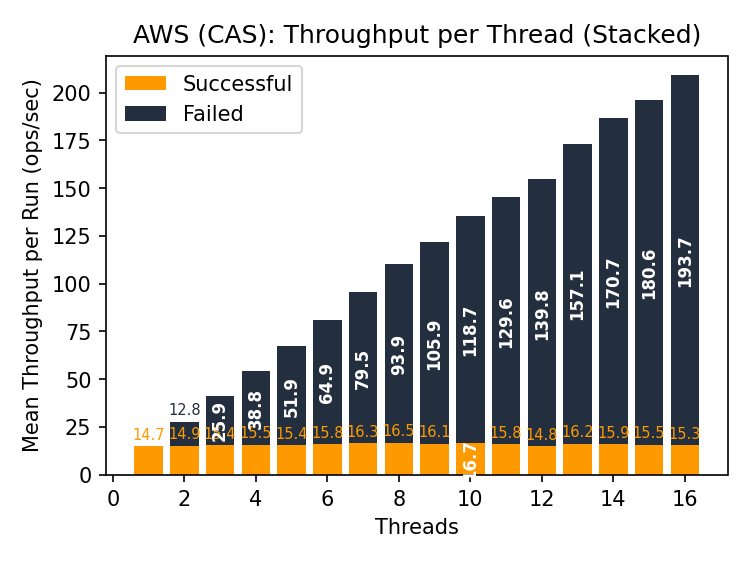

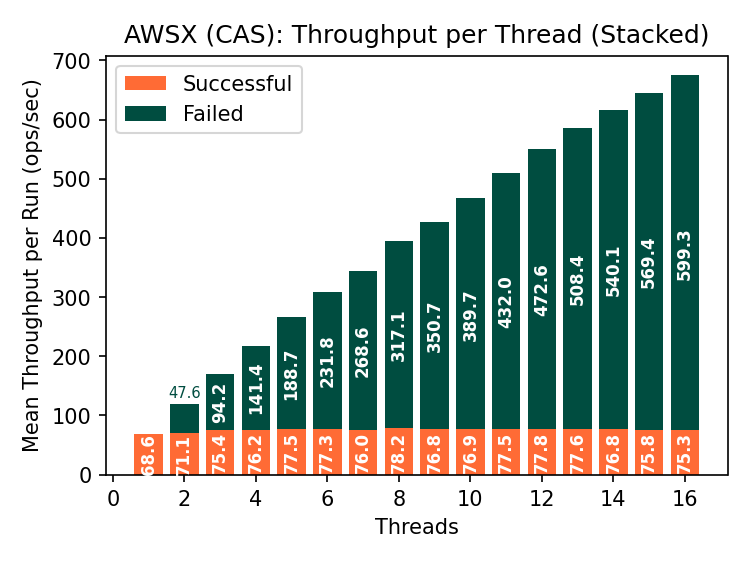

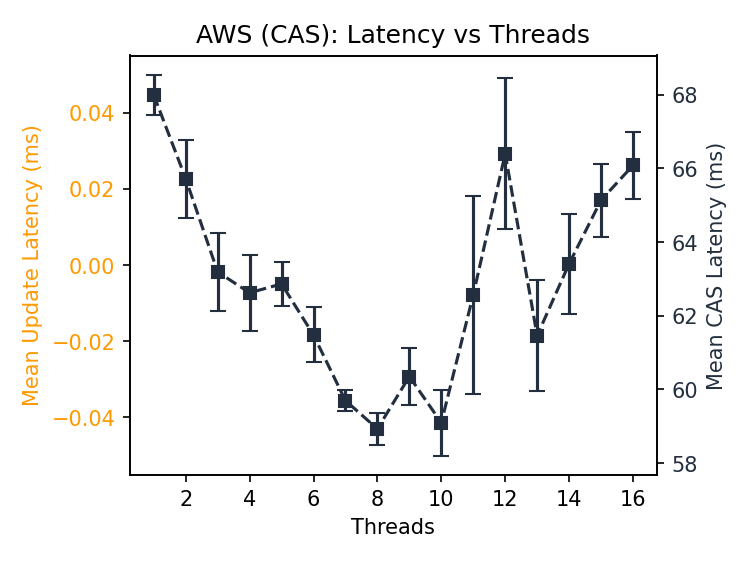

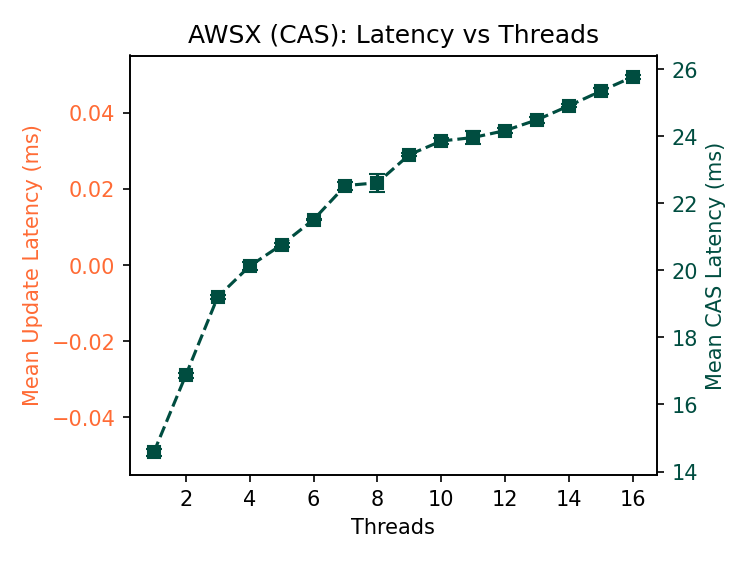

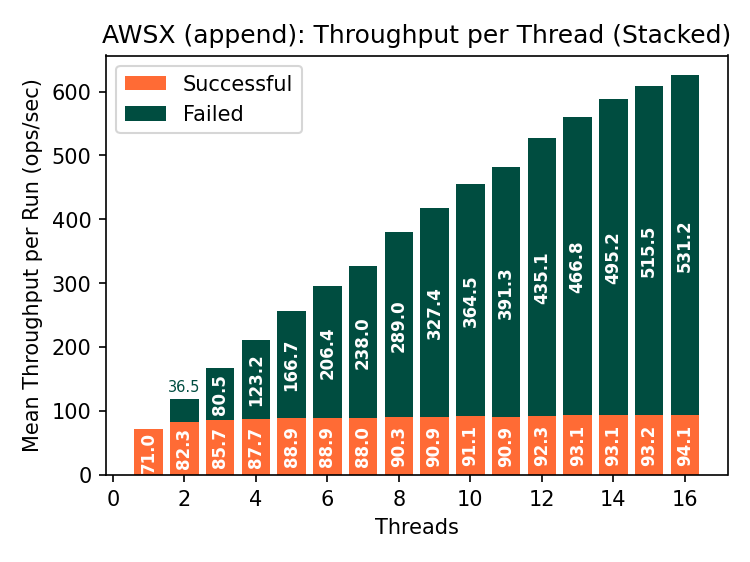

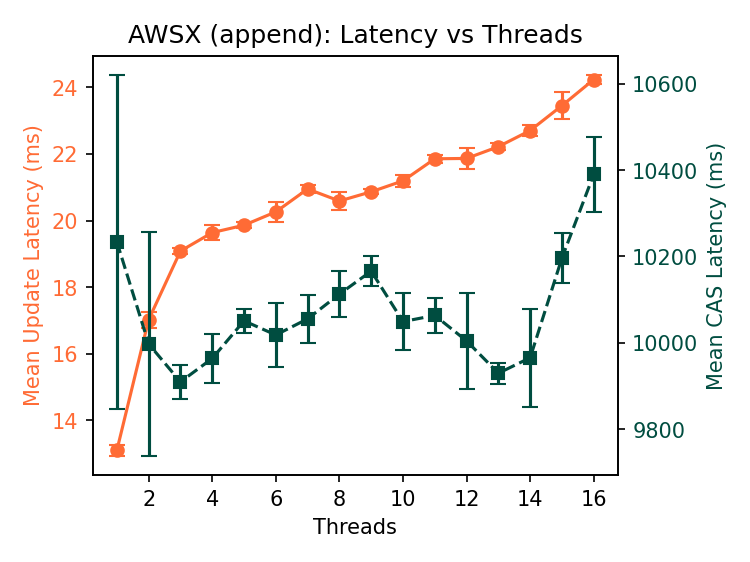

S3 CAS throughput is similar to Premium Azure Blob Storage. S3X CAS throughput is roughly 5x what we see in any other store. Again, most of the pipeline is wasted work (nearly 600 failed op/s!), but few Iceberg warehouses require this kind of throughput, even across tables.

The S3 and S3X latencies have low variance compared to GCS and Azure. Note that the CAS latency in S3 is within 10ms and in S3X the increase in latency is within 12ms, compared to hundreds of milliseconds separating min/max latencies in GCS and Azure. S3X is neither general-purpose storage nor magic- it restricts several S3 features to deliver this performance- but it delivers what it claims on its label.

Append

Next, let’s measure position-based append performance. There’s a long history of log-structured systems delivering high-throughput over append-only logs. Unfortunately, the prenominate constraints on position append make high throughput unrealizable in practice.

Azure

I’ll indulge in some eyeball statistics and call these pretty similar to the CAS throughput graphs above. The same read‑modify‑write cycle applies here. Because we do not retry operations in this benchmark, we’re not exercising the path where failed appends are retried at the new position; including retries would make latency a noisy proxy for retry rates.

For small objects, the virtues of append are not salient over CAS.

Latency of successful append operations is lower than CAS operations, particularly under contention. Only one or two runs on Azure appended enough data to reach the append limit, so we omit the interleaved CAS results.

S3 Express One Zone (S3X)

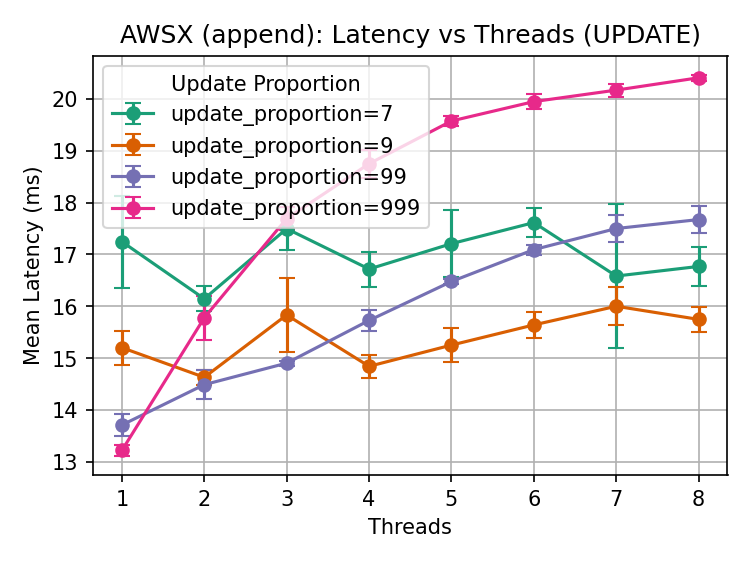

Append throughput is a striking ~90 ops/s, but CAS latency over 10 seconds? What is going on? Breaking down the latency of the CAS operation reveals that almost all the time is spent on the initial read of the object before the conditional write.

As we gradually add reads into the mix (0.1%, 1%, 10%, 30%), the mean latency of the CAS operation gradually increases as contention increases:

It’s not a coincidence that the append limits in S3X match the multipart upload limits (10,000 parts of at most 5GiB each)8. It appears that S3X accumulates parts (not enforcing the 5MiB minimum part size) until the object is read, and then lazily composes them into a single object. This is quite different from Azure’s implementation, which pays this cost eagerly for each append.

Discussion

First, some basic takeaways from the benchmarks. GCS was not designed to support this workload; the use case we’re interested in- linearizable writes on a single, small object- is explicitly throttled below a rate that could support even modest transaction rates. Azure Blob Storage and standard S3 sustain 10-15 conditional writes per second. The append implementations in both Azure and S3X exhibited anomalies in correctness and performance respectively, which complicates the implementation of optimistic protocols directly in these object stores.

Immutable data objects remain the core use case for object stores, even at premium tiers; stronger consistency and conditional operations are exciting, but insufficient to transform object stores into consensus systems.

Position Append is not (really) Multi-writer

Adding a “record append” API to object stores would allow the client to conditionally append not to a particular offset of a particular object, but to the end of a particular object… wherever it is.

Record append is not an easy API to use well, but it can improve throughput substantially9 and allow readers to tail the object coherently. Readers need to tolerate duplicates and implement framing for objects larger than the maximum append size (e.g., Azure Blob Storage’s 4MiB limit). To be fair: evidently the state of the art in position append isn’t that easy to use well either, at least for optimistic concurrency control.

To belabor a point: when a successful action invalidates all outstanding work, conditional operations create a lot of waste under load. Azure and S3 sustain steady throughput under contention, but as we see in these microbenchmarks, another service needs to be in front of the object store to batch operations and reduce conflicts to achieve higher throughput.

On the bright side, we can roll our own multi-writer append on top of conditional writes.

Emulating Record Append

Any service that guarantees the durability and ordering of writes can emulate record append on top of an object store supporting conditional writes. As in the (inferred) implementation of S3 Express One Zone append, primitives like multi-part uploads or composite objects in GCS can stitch together multiple writes into a single object. The trick is to get a consistent view for readers and lazily compact to the object store, coordinated using conditional writes.

AWS Object Lambdas can intercept GET, PUT, and LIST requests to S3 objects. If writes are funneled through a FIFO queue service like SQS, an object lambda can read a checkpoint in S3 and apply the queued appends to a particular object. On GET requests, the lambda replays queued writes over the base object from S3.

Asynchronously, the lambda function can conditionally write the compacted object (or append a prefix of the queue) to S3 and remove the corresponding entries from the queue. Other instances running concurrently may return a stale view, but never an inconsistent one. Conditional writes prevent compactions from losing state.

The object lambda adds cool points for being serverless and transparent to read-only transactions, but there’s no magic here. Clients could access the queue directly or any service could stand in front of S3 to batch and order writes.

Implications for Table Formats

So what does this mean for table formats? There are still opportunities to reduce write amplification, particularly using append. But for coordination through storage: any format needs to ensure real conflicts are rejected, making the rates measured here an upper bound on throughput under contention without an intermediary service.

Object stores are not (yet!) consensus systems. Data systems that use conditional writes should relegate them to a coarse, batch primitive for coordination, unless throughput demands are very low.

Thanks and Blame

Thank you Joe Hellerstein, Owen O’Malley, Tiemo Bang, Natacha Crooks, and Micah Murray for feedback on drafts. Ashvin Agrawal, Carlo Curino, Jesus Camacho Rodriguez, and Raghu Ramakrishnan at Microsoft (Gray Systems Lab) introduced me to table formats and helped shape many stages of a (now abandoned) research project on Iceberg. Mehul Shah’s prophecy steered me away from several pitfalls, except when I ignored his advice and fell into them anyway. Pavan Lanka and Sumedh Sakdeo offered useful insights into Iceberg workloads and ORC and Parquet internals, informing much of the work I’ll probably write about later. The misunderstandings and errors I managed on my own.

The Iceberg community deprecated its shared storage catalog (HadoopCatalog) last year, citing issues with atomicity in most storage systems. Clients now contact a catalog service to find the root of a table. Conditional writes could make a storage-only catalog possible, but we want to measure performance first to see if they are viable. ↩

Tachyon includes a wonderfully creative mechanism for tying recovery and priority to resource allocation. ↩

The Olympia catalog format also experiments with this approach in S3, using hint objects. The HadoopCatalog used a similar approach, but relied on

renameas its atomic, if-absent operation and consistent listings to find the tail. ↩As a side-effect, including this data in Iceberg

InputFileenforces its implicit immutability contract: if the object changes after being read, subsequent reads will fail the etag/generation check. ↩Multi-part uploads allow clients to upload a file in chunks that remain invisible until a (destructive) complete operation combines all the parts into a single object. Parts can be reordered after upload, but once the complete operation is issued the object is immutable. ↩

See CORFU for treatment of distributed log-based storage with record append semantics. ↩